Joseph Silverstein: Edward Elgar, Violin Concerto (conclusion); Boston Symphony, Colin Davis

From the Boston Symphony’s YouTube channel, here is the conclusion of the October 24, 1972 performance by Joseph Silverstein (who was then the Concertmaster of the Boston Symphony), of Edward Elgar’s Op. 61 violin concerto in B minor. The guest conductor is Colin Davis (who was knighted eight years later). By the way, at 1 minute 26 seconds, I believe I hear Colin Davis humming (or groaning) along, to bring out the big tune. (In Elgar, there’s usually a big tune.) The video runs from slightly before the (accompanied) cadenza through the end of the third, final movement.

Elgar’s violin concerto is one of the longest and most demanding violin concertos in the standard repertory. Its running time (modern recordings average circa 50 minutes) is about twice that of the most popular violin concertos (those of Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky). In addition to the demands Elgar’s concerto makes on the soloist’s endurance, his concerto presents many technical challenges. And portions of this video give an excellent birds-eye view of Silverstein’s rising to meet those violinistic demands.

Although Elgar’s rhapsodic style here, which is both discursive and intensely emotional, might take a bit of getting used to, I find that through the years, Elgar’s has always been one of my favorite violin concertos. And, as you will see as you read on past the jump link, I agree with my friend Bob Ludwig: that with Elgar, the interpretation makes the performance—this is not music that “plays itself.”

If I had to make a list of my favorite violin concertos off the top of my head, that list would look something like this:

TIED FOR FIRST PLACE:

Elgar, and Shostakovich 1

TIED FOR SECOND PLACE:

Sibelius, and Barber

TIED FOR THIRD PLACE:

Brahms, and Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy

FOURTH PLACE:

John Adams’ The Dharma at Big Sur

Five out of seven are twentieth-century works. Funny, that.

I love Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn, but for me, none of them have the impact of the twentieth-century concertos. (I can take or leave Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto.) So, with Elgar’s concerto tied for first place on my list, I urge you to devote some time to get to know it.

However, I understand that Elgar can be a tough sell. My friend Bob Ludwig relates:

For most of my life, I used to listen to Elgar and think to myself, I just don’t get it; this man simply does not resonate with me. Then, with the advent of the Internet, I started listening to BBC Radio 3, and of course they play a lot of Elgar and other English composers. One day, they were playing some Elgar, perhaps Falstaff, Enigma, or the Cello Concerto and BING! I heard a particular recording, and it all clicked into place! It seems for me that the proper performance of Elgar is vital to my appreciation of him, more than is the case with most composers.

One of the unusual features of Elgar’s concerto is that the cadenza, originally an improvised solo by the soloist toward the end of the first movement, was entirely written out by Elgar; it appears in the third movement; and it has its own accompaniment by the orchestral strings. I get a kick out of seeing the ranks of violinists with many of them holding their bows on their laps, so they can hold their violins like small guitars, the better to achieve the “thrumming” sound Elgar calls for.

A bit of a sidebar: Elgar was a Catholic in a time when Catholics in England really were second-class citizens. Edgar always regretted, with a sense of wounded pride, that as a Catholic, he could not be accepted at a University… “not accepted” not in the sense of “socially” not accepted; but rather, not accepted legally. As in, the path to the “schoolhouse door” was barred to him by law.

The irony being that a University musical education might have beaten the genius out of Elgar. Instead, the self-taught Elgar read scores (his father was a piano tuner who had opened a sheet-music shop), and there was nobody in authority to tell him that he should not wear his heart on his sleeve so much. I think the lack of a University education is why Elgar is Elgar, and not another Arthur Somervell. By which I mean no disrespect to a composer who wrote art songs in the tradition of Mendelssohn and Brahms. But it was not Somervell whom Richard Strauss toasted as “the first English [musical] progressivist.”

I can’t say whether Elgar’s sense of identity as a Catholic was the cause of his fascination with Italy and Spain. (I am sure that both Protestants and Agnostics enjoy the warm weather as much as anybody else.) But I can say that more than one other Elgar composition refers in some way to Italy, and also that the epigraph of the Violin Concerto’s score is in Spanish. Furthermore, I believe that the thrilling chordal figurations with rapid filligree embellishments in the violin solo part starting at 1 minute 17 seconds are meant to evoke the sound of a Spanish guitar.

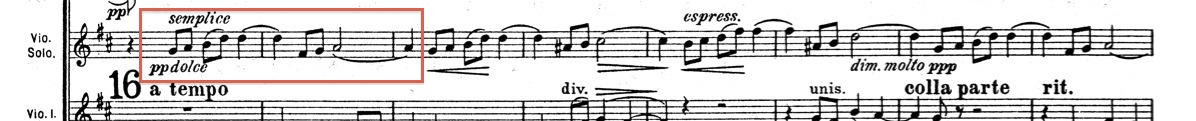

The technical challenges are remarkable; but I also think that much of the affection that people have for Elgar’s violin concerto hangs on the hook of a quiet melodic fragment (or gesture) that is as simple as a folk tune, the so-called “Windflower” theme. That theme first appears in the first movement, at rehearsal number 16:

and returns several times in the winding up of the third movement, the first being at 4 minutes 10 seconds. For me, the Windflower theme and its various workings-out are at the heart of Elgar’s concerto. (Another nifty, tremendously emotionally satisfying reprise is the way this violin concerto’s opening solo phrase, for which the only proper descriptor must be “enigmatic,” returns at 8 minutes 3 seconds.)

This 1972-vintage video (it seems) comes from a DVD appreciation of Silverstein’s career, and it also seems that the above excerpt is all that there is on that DVD. But I do recall, years ago, at least seeing notices that the entire performance was going to be released. Perhaps that fell through. A pity; because judging by its last 10 minutes, this was a superior performance. Bravo.

# # #