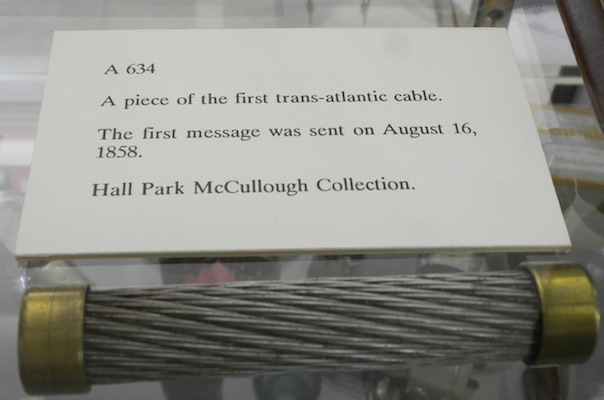

A Piece of the First Transatlantic Cable (1858)

My musically-astute friend and I found ourselves in mid-October enjoying the environs of Bennington, Vermont. An artistically-astute friend had some time before emailed me, urging me to see the Milton Avery exhibit going on at the Bennington Museum, and the timing worked out. (There’s an image of a wonderful Milton Avery painting after the jump.)

In addition to the Milton Avery exhibit (which just closed), the Bennington Museum permanently houses the largest Grandma Moses collection this side of Proxima Centauri (those clever aliens bought in big, when the market was really cheap). I must confess that my reaction to Grandma Moses always was, “OK, yeah;” but, seeing the paintings live, there’s really a lot more going on than a person might have gleaned from LIFE magazine, back in the day.

There was a vitrine holding artifacts from Grandma Moses’ painting workbench. I at first was puzzled by the glass jar of silver glitter, but it then dawned on me that she must have used the glitter to make her snowscapes sparkle; and, sure enough, the proof was hanging on the walls. The Bennington Museum asks visitors to refrain from photographing the Moses pictures, in that the Museum sells books and postcards. I imagine those constitute major sources of revenue, and so of course I complied.

However, there was no ukase prohibiting (non-flash) photography elsewhere; and so, when I was brought up short by seeing, in a vitrine in the hall dedicated to material culture and technology, an item the claimed to be a piece of the first transatlantic telegraph cable, I snapped the photo you see above.

History of technology lesson and philosophical musings, after the jump.

NB, the first transatlantic messages were exchanged more than two years before Abraham Lincoln took office!

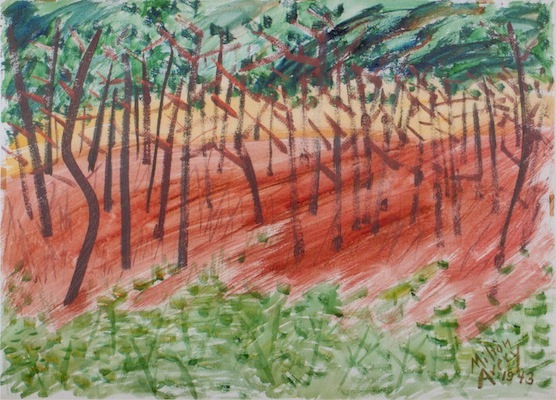

But first, the promised Milton Avery image. The linked-to Wiki is very much worth reading. Avery was a textbook 20th-century American Blue-Collar Intellectual. Mark Rothko praised Avery’s “gripping lyricism.” Art critic Hilton Kramer wrote:

He was, without question, our greatest colorist…. Among his European contemporaries, only Matisse—

to whose art he owed much, of course—produced a greater achievement in this respect.

My favorite image:

Milton Avery, Forest at Sunset, 1943.

Milton Avery, Forest at Sunset, 1943.

Collection of the Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation

The Bennington exhibit closed last week, but the catalog is available from Amazon—highly recommended.

And now, on to the transatlantic cable.

The history of material culture and technology (phonographs, radio, television, digital audio, and even the telegraph) has long been one of my major interests. The transatlantic cable has been a particular focus, because the early failures inspired British Post-Office employee Oliver Heaviside to invent the coaxial cable. Heaviside is one of the greatest but least-known mathematicians of the 19th century. Largely self-taught, it was Heaviside who reformulated James Clerk Maxwell’s unwieldy field equations into the form we know today.

The early transatlantic cable was armored but not electrically shielded. What was not realized at the time was that the passage of current through the cable from Ireland to Newfoundland induced a current in the surrounding water that slowed down the speed of the signal inside the cable, while adding distortion. The result was that Queen Victoria’s 98-word message of congratulations to President Buchanan (our most feckless President—so far) took 16 hours to send.

Oliver Heaviside recognized the problem of current being induced in seawater. By use of math alone, he designed a cable as a system with distributed inductance, allowing the cable to work efficiently in a manner analogous to a properly scaled organ pipe. In my own work designing audio cables, Heaviside has been an inspiration, at least to the extent that I believe that for digital signal transmission, the coaxial cable need not be re-invented, merely executed in as elegant a manner as possible.

So, back to the vitrine in Bennington. The outer layer of the cable is iron wire that has been twisted into yarns and the yarns twisted into iron rope. The iron rope armoring has no electrical function; it protects the cable as well as helping hold it together against the pull of its own weight as it is paid out from the cable-laying ship. It’s a shame there was no detailed information about the provenance of this artifact. My original thought was that after the first cable burned out (not recognizing the inductance problem, the operators kept increasing the voltage until the cable failed), as much of the cable as was easy to salvage was retrieved for scrap, and some pieces were saved as souvenirs.

But… this cable just looked too clean. Of course, a submerged cable could have been given a rigorous cleaning before the brass end caps were added. But my suspicion was that this was a small length of cable that had been intended for the transatlantic cable, but turned out to be surplus. Research revealed that indeed, a large quantity of leftover undersea cable was purchased by speculators in New York, who sold off short lengths as keepsakes. Even carriage-trade jeweler Tiffany & Co. got in on the act. The Tiffany cable souvenirs are distinguished by an embossed brass collar around the middle of the cable segment. The New York Historical Society holds a veritable crate-ful.

The Smithsonian Institute has a Tiffany example in its collection. In 1858, the Tiffany cable samples had a retail price of fifty cents each. A Tiffany transatlantic cable segment has recently been on offer on eBay for two thousand dollars. I think that that is awfully high, and that $500 is more realistic (or even generous), in that examples from a then-newly-discovered trove were on offer in 1976 at $100 each. There is an antiques dealer who appears to have stock, but, on a “price upon request” basis. (The reason there is so much bulk stock out there is that after the first transatlantic cable burned out, the bottom fell out of the souvenir market.)

I don’t think it is “the grapes were probably sour anyway” for me to suggest that there is a bit of a philosophical or epistemological problem lurking here. That is because, in a strict sense, these artifacts are things that never were part of the 1858 transatlantic cable.

These lengths of cable were never under water, and they never passed a message. Yes, they were manufactured in England for use in the transatlantic cable, and were duly put on a cable-laying ship, but… the cable length they were cut from was never actually used as a telegraph cable. Miles of cable were sold off as surplus. Unused surplus.

So, a fascinating memento; but also I think a case of, “So near, yet so far.”

# # #