Kansas Joe McCoy and Memphis Minnie: “When the Levee Breaks” (1929)

The infosphere is fairly crackling with the news that the current incarnation of the musical ensemble Fairport Convention Fleetwood Mac has notified one of its elderly members that his services will not be required for their upcoming world tour. More than 40 years later, Fleetwood Mac Drama still grabs headlines.

My favorite story about Fleetwood Mac is that during the Narcissistically tumultuous (my words, not theirs) recording of their 1977 mega-album Rumours, the two remaining founding members of the band (Mick Fleetwood and John McVie) repaired to the recording studio’s parking lot to get a breath of fresh air. One of these two gentlemen, not at all at peace with the way things were then developing (at the time, the tattered remnants of the original band were being either re-energized or supplanted by a pair of newcomers), said (or perhaps it is more accurate to write, “whined”) to the other,

“You know, we used to be a blues band.”

To which the other replied, “Yeah. But now, we’re rich.”

(That riposte refers to the fact that while the group was recording Rumours, their most-recently-released recording Fleetwood Mac, which was the first album with newcomers Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, was topping the charts and already throwing off so much cash that the previously hardscrabble members of the band were buying houses in Los Angeles. But: A blues record, Fleetwood Mac was not.)

That exchange says a lot about the endgame of British popular music’s fascination with American blues music.

Intriguing history, and sound bytes, after the jump link.

Eric Clapton; the original Fleetwood Mac; and Led Zeppelin:

What and where would they have been, absent their early exposure to 1950s-1960s LP transfers of decades-old 78rpm blues records? Clapton stated, “I spent most of my teens and early twenties studying the blues—the geography of it and the chronology of it, as well as how to play it.”

(The same holds true for bebop jazz—Clapton first came to prominence as a member of The Yardbirds, a blues band that was named after the late jazz legend Charlie Parker.)

Muddy Waters visited England in 1958, playing an electric guitar, rather than the acoustic guitar British blues fans expected. (Listen carefully, and you can hear the hinge of history softly creaking.) Waters’ high-energy amplified music inspired the creation of the bands Blues Incorporated (in 1961; which, along the way, at one time or another, employed four future members of the Rolling Stones, and two of Cream) and John Mayall’s Blues Breakers (in 1963; which employed the post-Yardbirds Eric Clapton, and also Peter Green, the founder of the first group to call itself Fleetwood Mac). Of Peter Green, B.B. King said, “He has the sweetest tone I ever heard; he was the only one who gave me the cold sweats.”

More: After Clapton left The Yardbirds, Jimmy Page (later of Led Zeppelin) and Jeff Beck served time there. Clapton, Page, and Beck all spent time in the same band—just think about that.

What all of this meant was that the blues would be the major influence on British rock music of the 1960s and 1970s. This had the effect of both sharpening the distinctions between the rock and pop genres, while putting rock on the path to spawning hard rock, heavy metal, punk, and other genres. Equally important, all the above meant that the sound of blues-influenced British rock would be that of a Gibson Les Paul solid-body electric guitar, played through an overdriven Marshall amplifier.

One can imagine a wall-sized genealogical chart that represents all the fascinating apprenticeships, influences, and connections from 1950s England on, that, to a greater extent than anything else, determined what Americans would hear on their FM radios in the 1970s. (And perhaps something like that has already been created.) But for me, the more interesting thing is the “Why?” of it:

Why did Britons from nearly all walks of life and regions adopt American blues as their musical language?

I think I have at least one valid answer.

Earlier this year, I wrote about the Profumo Scandal, the early-1960s political crisis that was the death knell of the old Tory regime—when the Tories eventually returned to power, it was under the egalitarian or at least meritocratic banner of Margaret Thatcher, “the Greengrocer’s daughter.”

In his excellent Profumo Scandal book An English Affair, Richard Davenport-Hines asserts that the defining characteristic of English public life in the 1950s was hypocrisy. Classism, male Chauvinism, conformity, and complacency were all parts of that toxic mix; but the top note was hypocrisy. John Profumo had been cheating on his wife for years before he stumbled onto the front pages of the tabloids. Everyone who was anyone knew it, but said nothing. And Profumo’s secrets were not the only “open secrets” in British society.

In the context of a closed-in society that was obsessed with minute distinctions in class rank, where appearing in public in shirtsleeves could be regarded as a radical break with tradition, I think that the obvious instinctive response to such overwhelming hypocrisy would be, to seek out and embrace authenticity.

For British young people sick of hypocrisy, the authenticity (as well as the otherness) of American blues could be a cleansing and liberating force.

Photo credit: www.knowlouisiana.org

Photo credit: www.knowlouisiana.org

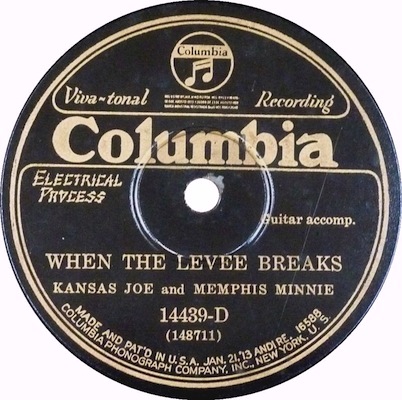

Lizzie Douglas (1897-1973), known as Memphis Minnie, was a blues guitarist, composer, and singer who recorded more than 200 78rpm sides. She and her husband Kansas Joe McCoy recorded “When the Levee Breaks” in 1929. The song was inspired by the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

The Great Mississippi Flood displaced 325,000 people (69% of them African Americans) into relief camps that were often located on top of levees. The Flood had major lasting impacts on American society, the most important of which were accelerating the Great Migration of rural Southern African Americans to Northern urban centers, and African-American disenchantment with the Republican Party (which was caused by the Hoover administration’s failure to keep the promises by which it had won Northern African-American votes).

The disc’s label (above) specifies “Guitar accomp.” While I have not been able to find any first-hand reports about the recording session, what is most likely is that Minnie played lead guitar, while her husband played rhythm guitar and sang. The instrumental texture of the song is strangely jaunty for a song about fears that a flood would take everything, including perhaps one’s life. Furthermore, McCoy’s singing is perhaps a bit understated; but it also could be the case that his low-key-ish delivery is what gives the song its authentic touch of poor-folk fatalism.

Truth be told, I would most likely not know about “When the Levee Breaks” except for Led Zeppelin’s 1971 cover, on their fourth album, the one that contains “Stairway to Heaven.” Two songs more dissimilar from each other than Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” and their “When the Levee Breaks” cover, it would be hard to imagine.

Whereas the original “When the Levee Breaks” is almost perky in tempo and matter-of-fact in delivery, Led Zeppelin’s re-working is dark in tone (the song was recorded at one pitch and tempo; but in mastering, the analog tape was slowed down to make it sound muddier), symphonic in its aspirations, and operatic in its delivery.

The phenomenon of “British Blues” not only put rock on a decidedly different path from pop (whereas the Beatles had usually managed to straddle that divide); the commercial success in America of British bands such as Led Zeppelin served to introduce American blues to demographic groups that had rejected (or had been incurious about) the original artists and songs.

Early on in this essay, I posed the rhetorical question, whither Eric Clapton, the original Fleetwood Mac, and Led Zeppelin without their exposure to U.S. country-blues recordings from previous decades?

I end by asking, what and where would American blues proponents such as Stevie Ray Vaughan have been, absent British musicians’ examples?

Both versions of “When the Levee Breaks” are available via multiple YouTube postings, so, here is a minute or two of both.

“When the Levee Breaks,” Kansas Joe McCoy and Memphis Minnie (1929)

“When the Levee Breaks,” Led Zeppelin (1971)

# # #