“The Song of Names” (film)

Center: Dovidl (played by Luke Doyle)

© Sabrina Lantos. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics.

Classical-music fans, especially fans of the violin and its literature, will want to know about the upcoming (opening in selected cities December 25, 2019; nationwide in January) big-screen theatrical release of the film The Song of Names, based on Norman Lebrecht’s prize-winning novel of the same name. The director is François Girard (The Red Violin, Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould); for that reason we can have a high degree of confidence that great care has been taken in getting the musical details right. But all that is not to say that people whose primary musical orientation is other than classical will not also appreciate the film. The plot is compelling, the characters are intriguing, the cinematography is atmospheric, and the film score is by Howard Shore, of Lord of the Rings fame.

Here’s what the film’s US distributor Sony Pictures Classics says about the setup of the film’s action, much of which is told in flashbacks:

Martin Simmonds (Tim Roth) has been haunted throughout his life by the mysterious disappearance of his “brother” and extraordinary best friend, a Polish Jewish virtuoso violinist, Dovidl Rapaport, who vanished shortly before the 1951 London debut concert that would have launched his brilliant career. Thirty-five years later, Martin discovers that Dovidl (Clive Owen) may still be alive, and sets out on an obsessive intercontinental search to find him and learn why he left.

What interests me most, of course, is how successful the production crew has been at allowing the audience to suspend disbelief and accept that the actors on screen are actually playing the violin. Based on what I have seen, I think they have done a very impressive job. Further explanation, the trailer, and a mini-feature on the teenage actor who is also a genuine violin virtuoso, after the jump.

Left to Right: Dovidl (played by Luke Doyle), François Girard (Director),

Martin (played by Misha Handley) © Sabrina Lantos. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics.

The story that is told through flashbacks is: shortly before the outbreak of the second World War, the father of Dovidl, a nine-year old Polish Jewish violin prodigy, brings him to London in search of a safe home. The father entrusts his young son to a Gentile music publisher and his family, and returns to Poland intending to ensure the safety of his wife and daughters. But he is too late, and they all are killed, leaving the young boy in London an orphan in a strange land. The publisher lavishes attention and money on the orphaned boy, which obviously is a burden on his own son of the same age (Martin), who has become friends with the charismatic young musician. So, each of the two major characters (Dovidl and Martin) need to be played by three actors: first as pre-teenagers and teenagers; then as young men; and then as mature men.

The fact of the matter is that the native audio recorded as a movie scene is being filmed is not usually what is heard in your local cinema. As the scene is being shot, there will be noise from production equipment, traffic noises, airplane flyovers, or sneezing extras. After filming, a supervising sound editor goes through all the native dialog and decides how much (if any) can be used. Then, as needed, the dialog is re-recorded on a sound stage, or in a vocal booth.

The same holds true for scenes where an actor is singing or playing an instrument. The vocal part or instrumental performance is re-recorded under optimal conditions, and then dubbed back in. Therefore, the usual challenge in casting the three actors for each character would be not so much to find actors who could play the violin (or the piano, in Martin’s case) to a high degree of professional facility. The challenge was to find actors who could be taught to look convincing. This was accomplished in the cases of Clive Owen and Jonah Hauer-King, who play Dovidl at 55 and as a young adult, by engaging British violinist Oliver Nelson (who shares a name with an important jazz arranger of the 1960s) to coach them.

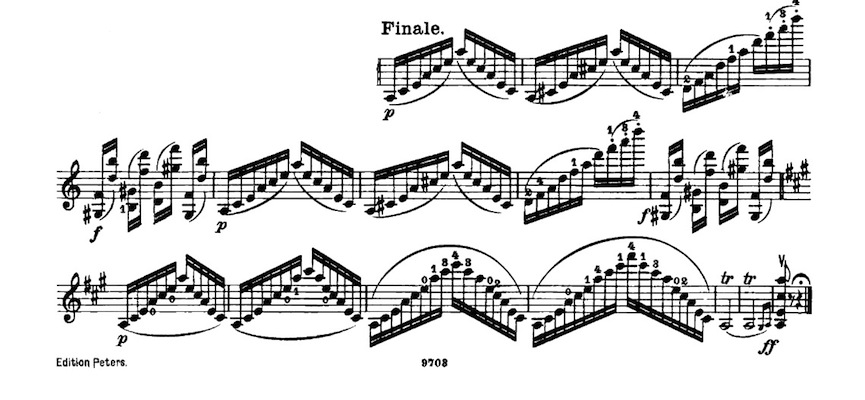

However, I think that the producers and director really lucked out with young Luke Doyle, who plays Dovidl from ages 9 to 13. Luke Doyle is the genuine article as a young violin prodigy. The brief video clip below is of an impromptu face-off between two young violinists in an underground bomb shelter during the London Blitz. The music is the last section (“Finale”) of Paganini’s 24th Caprice.

Now, here is where the two technical paragraphs appearing above become very relevant. Luke Doyle is actually playing the music on his violin—some of the camera angles clearly show that his fingers are hitting all the notes perfectly; it’s just that the audio tracks with Luke’s playing on them ended up on the cutting-room floor, and were replaced by established violin star Ray Chen‘s studio performance. For all sorts of valid reasons, I am sure. (The camera angles for the other young violinist are more oblique, and less revealing.)

Luke Doyle is now, I believe, 13 years old. His local television service did a brief segment on him:

We're not 100% sure what we were all doing at the age of 13 – but we're sure it wasn't mastering the violin and starring in a movie with some Hollywood A-Listers!

Amazingly though, that's what Luke Doyle from Glastonbury has done… pic.twitter.com/HCHojTpRMg

— ITV News WestCountry (@itvwestcountry) November 11, 2019

Toward the end of this brief profile, back at school, Luke plays a bit from the third movement of Max Bruch’s G-minor violin concerto. I’m impressed. BTW, I applaud the use of a higher chinrest rather than a shoulder pad. From that, and from his generally relaxed posture, I infer that Luke’s teachers have been sensitive and enlightened. Praise and honors to them, and to his parents. I wish Luke the best… but with the thought in mind that just possibly, it might be the case that the best thing for his future happiness might not be getting on the violin-competition treadmill. But that’s just me.

Here’s the film’s official trailer.

Here are reviews (with plot spoilers) from The Hollywood Reporter and BlogCritics.

With the proviso that the film will doubtless deliver an emotional wallop (so perhaps this is not the ideal film for a first date), highly recommended.

UPDATE: A very favorable review from the Los Angeles Times is here.

# # #

John, Thank you for encouraging attendance at (or streaming of) what would look to be a solid of a movie, certainly for us classical music types. Beyond that, your paragraph on production sound and post-production processing cuts close to my heart. That problematic environment has become for me a subject of intense scrutiny and even of some invention. My dominant aesthetic principle requires much greater use of real-time acting and playing to reduce the appalling artificiality of dubbed (“post-pro”) sound and performance. The proffered solutions avoid the usual approaches of “noise reduction” and sectioned insertions. If anyone would care to explore these critical matters with me, I am @gmail.

Dear Clark,

Thanks for posting! For those not in the know, Clark’s book on the psychoacoustical audibility of acoustical phase inversion was published by the Harvard University Press.

I want to assure readers that within the limitations of post-production technology, the sound substitutions in this movie, as far as I can tell from close listening on headphones to the YouTube excerpts, are about as good as they ever get. So, in a megaplex cinema, any infelicities might get lost in the shuffle.

I once did some sound tests on the immense soundstage where some of the interiors for the “Amistad” movie were shot (Sonalyst Studios, Waterford CT). It would be like playing solo Bach in a Zeppelin hangar.

ATB,

john