Month: September 2018

Guest Post: An Open Letter to the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis

Photo courtesy of Bein & Fushi.

Guest Post:

An Open Letter to “The Indianapolis”

From The Mendtchaik Madman

I am informed via my Internet connection that the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis (heretofore also known as “IVCI”) now wishes to be known as “The Indianapolis.” OK!

One of my mentors in the business of business once told me that the only thing worse than forgetting to listen to the customer was choosing an image makeover instead of improving the product.

Whether the process by which violin competitions turn out their product really needs improving is, without doubt, a matter of dispute. Not too long ago, Norman Lebrecht postulated that unlike piano competitions, violin competitions do not “make stars.”

At the time Mr. Lebrecht’s post went up, I disagreed.

However, now that I have paid close attention to The Indianapolis 2018, I must admit my mistake. The violin-competition system is broken, and it must be taken apart and put back together in a different shape.

Indianapolis International Violin Competition Live Video Streaming

One of the most important international competitions for young (ages 16 to 29) violinists takes place in the United States every four years. (The other top-tier classical-music competitions that include violinists, Moscow’s International Tchaikovsky and Belgium’s Queen Elizabeth, also run on four-year cycles.) While one might expect the US entry on that list to be hosted in California or New York, the venue is: Indianapolis, of 500-mile auto-race fame—and for excellent reasons.

Indiana University (Bloomington) has one of the most outstanding music schools in the world, and that is where violinist Josef Gingold brought his remarkable career to a conclusion, as a Distinguished Professor of violin. Gingold was born in Poland in 1909. When his family came to America, his violin studies continued with Vladimir Graffman, father of the pianist Gary. Gingold returned to Europe in 1927 to study with Eugene Ysaÿe, a towering figure in the history of the violin. A composer as well as a virtuoso, Ysaÿe was the dedicatee of the Franck Sonata (1886), and led the first performance of Debussy’s string quartet (1893).

Gingold came back to the US and tried to build a career in the depths of the Depression. He contented himself with Broadway pit-orchestra work until 1937, when Arturo Toscanini hired him for the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Gingold’s career progressed to positions as Concertmaster of the Detroit and then Cleveland orchestras, the latter at the request of George Szell. Gingold remained with the Cleveland Orchestra until 1960, when he joined the music faculty of Indiana University. In 1982, Josef Gingold provided the artistic guidance for the founding of the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis.

I think that the Indianapolis violin competition has succeeded to the impressive extent it has because of three factors. One, Josef Gingold’s worldwide reputation, not only as a performer and teacher but also as a fair-minded member of the juries of all the major violin competitions (including the Tchaikovsky and the Queen Elizabeth) made some degree of early success a relatively safe bet. (However, sustaining an enterprise into its fourth decade requires much more than that.) Two, the synergy with Indiana University’s music school, which attracts students from all over the world. Third, and perhaps most importantly: if people started a violin competition in New York or Los Angeles, it would be just one more cultural event in a market crowded with them. Whereas in Indianapolis, an international music competition does not have much local same-tier competition for attention, donors, and volunteers. (I think the same thing can be said for Fort Worth and the Van Cliburn competition, in the piano world.)

This year’s Final round of competitors’ performances runs from Wednesday through Saturday, September 12 through 14. The preliminary rounds and semi-final round video streams are now available for delayed viewing (scroll down for the preliminaries), and the final rounds will be streamed live. The audio and video production values are excellent, and the playing has been of a very high standard. The finalists are: Ioana Cristina Goicea (Romania); Risa Hokamura (Japan); Luke Hsu (US); Anna Lee (US); Shannon Lee (US/Canada); and Richard Lin (Taiwan/US).

# # #

The Saddest Song

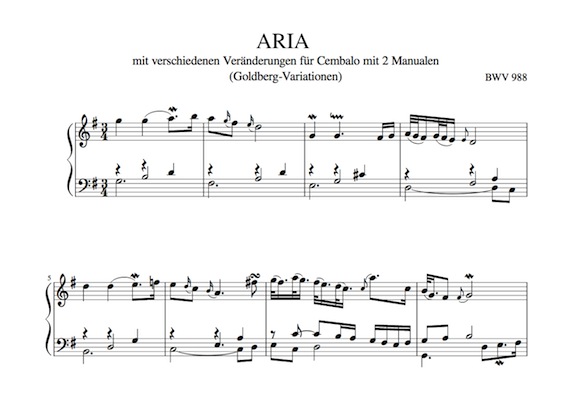

Open Goldberg Variations, Werner Schweer, editor.

Open Goldberg Variations, Werner Schweer, editor.

Listening to “happy” music can make one feel happier. However, instead of always making people feel worse, listening to sad music often brings on a state of “paradoxical pleasure.”

I am not saying that listening to sad music in and of itself makes people happier. What I am saying is that listening to sad music can evoke a sequence of very complex emotions. Furthermore, many people regard experiencing that kind of a cascade of metamorphosing emotions as “pleasurable.” (Or perhaps, just as a relief.)

The somewhat waffle-like language employed above is in recognition of the fact that many people experience the same music in different ways. By the way, the sequence of emotions Shock/Disbelief/Anger/Despair formerly was called The Four Stages of Saab Ownership. “What do you mean, my engine’s harmonic balancer was held on with glue?”

I think whether the precise emotional mechanism (and what a silly word “mechanism” is to use, in this context) is transference or catharsis or a feeling of empathy will just have to remain a mystery of the human soul. But from the earliest times, serious thinkers (from Aristotle to Schopenhauer) have always recognized that the power of sad music (and also of literature and drama) does not lie in its merely making people feel sadder than they had been.

A recent BBC Culture article asks whether data diving can “reveal” the “Saddest Number One Song Ever.” I think that that article itself reveals the multiple, perhaps even fatal, limitations of such an approach.

If I had to pick one song known to me as the saddest ever (which avoids the major problems associated with judging the quality and the qualities of songs by things like Billboard charts or Grammys), that would be the “Aria” from the Goldberg Variations. The Goldberg Variations might not have words, but right at the top of the score it says “Song” (albeit in Italian).

Song samples and more pondering, after the jump. Continue Reading →