Category: Piano

Noam Sivan: Improvisations upon the Goldberg Variations, BWV 988

I am indebted to David P. Goldman‘s wonderful Tablet magazine article on the place of classical music in Israeli society for introducing me to the young pianist Noam Sivan, who is recovering the lost art of classical-piano improvisation.

Born in 1978, Sivan has taught at the Curtis Institute and the Juilliard School. Currently he is Professor of Piano Improvisation at the State University of Music and Performing Arts Stuttgart, where he has opened a Master’s-Degree program in classical-piano improvisation.

His album Chopin & Improvisations is downloadable from his website.

# # #

Joanne Polk: Louise Farrenc Etudes & Variations for Solo Piano

Joanne Polk: Louise Farrenc: Etudes & Variations for Solo Piano

Steinway & Sons CD (STNS 30133) and MP3 downloads available from Amazon

Hi-Res downloads (24-bit/96kHz stereo AIFF, ALAC, FLAC, and WAV) available from HDTracks

Streaming available from Tidal (and others)

Release date: February 7, 2020

Recorded May 15-17, 2019, at State University of New York Purchase College Performing Arts Center Recital Hall. Producer and recording engineer: Steven Epstein. Total time 70 min. 05 sec.

Here’s another winner of a recording from Steinway and Sons. As we have learned to expect, the recorded sound is superb.

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875), especially for someone who today merits not even the proverbial asterisk in most music guidebooks, had an amazing career. Judging from this release, Farrenc’s music is firmly in the mid-19th-century Romantic virtuoso-piano tradition of Liszt and Chopin, even to the extent of including crowd-pleasing paraphrases of (or, variations upon) opera themes or arias by Bellini (Norma) and Meyerbeer (Les Huguenots).

All of which pianist Joanne Polk presents with facility, fluidity, dispatch, and élan. To get a French word in there. (And also, with joie de vivre.) The Les Huguenots piece is a corker: Imagine if Franz Liszt had gone to town on Martin Luther’s “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” (Oops; perhaps Liszt actually did that. Dunno. Long ago, I decided that FL was, for the most part, not my cup of tea; so I might have a bit of a blind spot there.)

Ferranc studied theory and composition with Anton Reicha, one of Berlioz’ teachers. She became the first female professor of piano the Paris Conservatory in 1842. Her Thirty Etudes were adopted as required repertory for piano students there in 1845. Her published compositional output included chamber music as well as three symphonies, all of which were performed.

Therefore, one might feel the need to ask why her music has spent so much time languishing in obscurity.

Musings, ponderings, and sound samples, after the jump. Continue Reading →

How China Made the Piano Its Own

Yuja Wang, courtesy of Medici TV

Yuja Wang, courtesy of Medici TV

This is a first—I can’t ever remember reading an article in The Economist that brought tears to my eyes… . The article in question is, to use academic terminology, a “reception history” of the piano in Chinese culture from the mid-19th century to the present. Here’s the vignette from China’s 1966-1976 “Cultural Revolution” that brought out my handkerchief:

Lu Hong’en, the conductor of the Shanghai Symphony, was thrown into a cell. He continued to hum Beethoven there. After he tore up a copy of Mao’s “Little Red Book,” he was sentenced to death. Lu told a fellow prisoner: “If you get out of here alive, would you do two things? Find my son, and visit Austria, the home of music. Go to Beethoven’s tomb and lay a bouquet of flowers. Tell him that his Chinese disciple was humming the Missa Solemnis as he went to his execution.” Lu was shot within days. His cellmate reached the Viennese grave three decades later.

You will have to read the rest of the article for yourself, here (you probably will have to register to read five free articles a month). I consider this article to be required reading for cultural literacy in classical music in today’s world. The author or authors point out that China is not only turning out star performers (such as Yuja Wang, pictured above); the creation in China of music for the piano has reached critical mass.

The one caveat or clarification I want to offer is that the article states, without elaboration, that the state-run piano company Pearl River (the world’s largest producer) “builds for Steinway.” That statement is, in my opinion, accurate; but also, potentially very misleading. Pearl River does not make Steinway pianos, or even parts or components for Steinway pianos.

What is going on here is that the Steinway company wants its dealers also to be able to offer pianos that are more affordable. Pianos with, if perhaps not Steinway’s imprimatur, at least their nihil obstat. Those brands are the “Boston” and “Essex” pianos. The Essex pianos are “designed by Steinway” and sold by Steinway, but manufactured in China by Pearl River.

The linked-to article also includes an embedded playlist of relevant music and performances, which in and of itself is a reason to click through.

# # #

Cole Porter on a Steinway, vol. 1

Various: Cole Porter on a Steinway, vol. 1

Solo-piano transcriptions of show tunes by Cole Porter

Steinway & Sons catalog number 30116

Release date: December 6, 2019

Recorded at Steinway Hall, New York City, July 2014-April 2019.

Well, here’s a real winner!

Steinway & Sons’ piano recordings—especially the ones that they themselves produce and engineer at the new Steinway Hall performance and recording facility in New York City—are of reliably superb audio quality. That said, I hasten to point out that Steinway’s releases that were not recorded in Steinway Hall are often (but not always) just as good in terms of sound quality; they are merely “different.”

I think that the Steinway recordings made at the Shalin Liu performance hall in Rockport, Massachusetts are objectively as “good” as the Steinway Hall ones. Subjectively, I have a (slight) personal preference for the slightly more distant and bloom-y sound of Shalin Liu. If anyone prefers the slightly more in-focus Steinway Hall sound, I will not lose any sleep.

I also must point out that the sonic differences I am noting (and such is the case with many audio differences) are minor; they might not reveal themselves to casual listeners who only give a casual listen.

By this point, Steinway has released well over 100 CDs. Not all of them have totally won me over to their artistic standpoints (of course, such are matters of taste, and you are free to disagree). But… when the stars and planets line up as they do here… Wow!

This collection of solo-piano treatments of famous Cole Porter show tunes (by three different pianists, Adam Birnbaum, Jed Distler, and Simon Mulligan) presents, in spot-on high-resolution (24/96) sound, standout Cole Porter interpretations that range from the wistful and pensive to the liltingly bouncy. All delivered via sloshingly-full buckets of piano technique and always with a refined musical taste that might have made Cole Porter smile.

You can hear the entire album right now, at no charge via Steinway Streaming.

Cole Porter on a Steinway, Vol. 1 goes on sale December 6, 2019 (downloads only; mp3 on Amazon; 24/96 FLAC on HDTracks).

More pensations, and sound samples, after the jump. Continue Reading →

Steinway & Sons Streaming: An Excellent No-Cost Music Source

Steinway & Sons’ Spirio Playback Piano.

Steinway & Sons’ Spirio Playback Piano.

Image courtesy of Steinway.

I felt a rueful twinge when legendary piano builder Steinway & Sons took itself private and as a result was de-listed from the New York Stock Exchange. My nostalgic or sentimental reason was that Steinway & Sons’ NYSE stock-ticker symbol long had been LVB, an homage to Ludwig van Beethoven. Beethoven’s piano sonatas are generally regarded as the distilled essence of greatness in piano music.

Apart from that, as far as I can tell, jumping out of the goldfish bowl that is the NYSE has done wonders for Steinway. In 2014, Steinway came out with the Spirio, a piano (available in two sizes) that includes the most sophisticated piano-playback technology (a non-MIDI system) ever to reach commercial critical mass. More recently, Steinway has begun offering a record-and-playback version of the Spirio. Steinway’s biggest challenge at the moment is building enough Spirio pianos to meet the demand. Good for them.

Under New Management, Steinway also launched their own CD label (they have also released a few SACDs). They embarked upon an ambitious recording agenda, for which they built a new, state-of-the-art performance-and-recording hall. So that you can hear the complete recordings before you buy the CDs or download the audio files, Steinway has created a dedicated streaming site that offers commercial-free play of complete albums from Steinway & Sons Recordings. There are also informative reviews posted for many of the albums. Steinway & Sons CDs are available from Amazon; hi-res files, from 24/44.1 to 24/192 (varying by title) are available from HDTracks.

I asked Eric Feidner, Steinway’s VP for Music, Media, and Technology, to tell me about what “getting into the record business” has meant for the 166-year old firm.

At Steinway, our very long history with performing artists goes back to the 1800s, with legendary pianists such as Anton Rubinstein and Ignace Paderewski. In recent decades, the “Steinway Artist” program has been a central part of the company. We started the record label about 10 years ago as a natural outgrowth of our relationships with Steinway Artists.

As we moved into the development of the Steinway Spirio, we faced a critical need to create a catalog of “high resolution” music to embed in the world’s finest player piano—we send our Spirio owners new playlists every month. Because there was no such content available elsewhere, we had to build our own. There are now close to 4,000 works in the Spirio catalog.

The Spirio piano’s development and the Spirio catalog’s development processes inevitably became symbiotic with the record label, as through these, we developed techniques to produce commercial audio recordings with far greater efficiency and with remarkably consistent levels of technical and sonic quality. Making recordings and building pianos are now very closely intertwined at Steinway & Sons.

After the jump, recommendations for a baker’s dozen (13) great CDs that you can hear in their entirety at no cost! Continue Reading →

Khatia Buniatishvili: F. Liszt, “Ständchen” (piano transcription after Schubert)

Khatia Buniatishvili (born 1987) chose the music of Franz Liszt for her 2011 Sony Music début CD. So I think it fair to assume that Liszt holds a special place in her heart (an assertion that is validated by a quick perusal of her heart-on-sleeve personal website). My impression had been that she was a pianist who felt the gravitational pull of the monuments of the virtuoso repertoire–her website’s home page features an announcement for her recent recording of Rachmaninoiff’s second and third concertos.

So I was as surprised as I was delighted (and moved) by stumbling upon a live-performance video of her (I surmise) giving a pensive encore (I assume, before the expected blazingly-fast, final encore) at the Verbier Festival: Liszt’s restrained and wistful embellishment upon Schubert’s D 957 No. 4 “Ständchen” (“Serenade”)(“Leise flehen meine Lieder”), which is one of the small quiet glories of the vocal repertoire.

My beau-idéal in pianism is Ivan Moravec; and I must say that this clip is the only thing I have heard from a young player before the public today that reaches Moravec’s level of inwardness and quiet contemplation. Brava.

# # #

An Open Letter to the Rhode Island Arts Community

Aaron Diehl with the New York Philharmonic.

Aaron Diehl with the New York Philharmonic.

Re: Aaron Diehl, Concert with the Rhode Island Philharmonic, October 20, 2018

I am aghast and outraged by Channing Gray’s ignorant, small-minded, and perhaps even racist review in the Providence Journal.

This insanity has to stop. (If people are more comfortable with the word “dysfunctionality,” that is OK by me. But nobody should be comfortable with the current state of affairs.)

As far as I know, Channing is a failed keyboard performer who (based on a mountain of evidence), has never gotten over it. Furthermore, I surmise that Channing’s specialty was early keyboard music (he played the organ at the wedding of an acquaintance of mine–that’s called gigging). In his review of Aaron Diehl’s performance, he wore his classist ignorance of jazz on his sleeve.

Aaron Diehl’s performance was the most magnificent piano performance I have ever heard from a soloist with the RIPO. From the first notes it was obvious that Mr. Diehl had not only enviable technique, but also something that is increasingly rare these days, that being: Excellent musical taste. Continue Reading →

Q & A with Aaron Diehl

Aaron Diehl’s 2013 CD The Bespoke Man’s Narrative, his début on Mack Avenue Records, fell like a thunderclap upon the jazz landscape, reaching No. 1 on the JazzWeek Jazz Chart.

Something about the advance publicity must have caught my eye or ear, because I asked for a pre-release press copy of the CD. Upon playing it, I was so gobsmacked that I asked my friend and colleague Steve Martorella to come over to listen to it. Steve was a protégé of Leonard Bernstein’s, and his principal piano teacher was Murray Perahia, so I think that it is fair to say that Steve probably knows a little about piano playing. While he was listening to the climax of Diehl’s piano-trio version of “Bess, You Is My Woman Now,” Steve was definitely getting tears in his eyes. His comment: “I didn’t know that there was anyone new who could play like that.”

In due course my comments on The Bespoke Man’s Narrative appeared in Stereophile magazine. Since then, Aaron Diehl has released another small-group recording as well as a solo project. Next weekend (October 19 and 20) he will appear with the Rhode Island Philharmonic (under the direction of Bramwell Tovey) playing Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. Mr. Diehl graciously agreed to answer a few questions.

Questions, answers, and a sound sample can be found after the jump. Continue Reading →

The Saddest Song

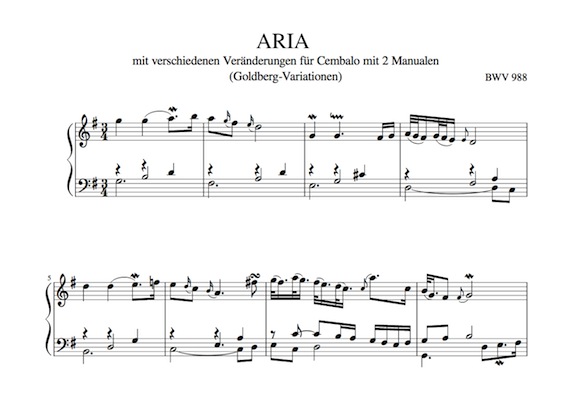

Open Goldberg Variations, Werner Schweer, editor.

Open Goldberg Variations, Werner Schweer, editor.

Listening to “happy” music can make one feel happier. However, instead of always making people feel worse, listening to sad music often brings on a state of “paradoxical pleasure.”

I am not saying that listening to sad music in and of itself makes people happier. What I am saying is that listening to sad music can evoke a sequence of very complex emotions. Furthermore, many people regard experiencing that kind of a cascade of metamorphosing emotions as “pleasurable.” (Or perhaps, just as a relief.)

The somewhat waffle-like language employed above is in recognition of the fact that many people experience the same music in different ways. By the way, the sequence of emotions Shock/Disbelief/Anger/Despair formerly was called The Four Stages of Saab Ownership. “What do you mean, my engine’s harmonic balancer was held on with glue?”

I think whether the precise emotional mechanism (and what a silly word “mechanism” is to use, in this context) is transference or catharsis or a feeling of empathy will just have to remain a mystery of the human soul. But from the earliest times, serious thinkers (from Aristotle to Schopenhauer) have always recognized that the power of sad music (and also of literature and drama) does not lie in its merely making people feel sadder than they had been.

A recent BBC Culture article asks whether data diving can “reveal” the “Saddest Number One Song Ever.” I think that that article itself reveals the multiple, perhaps even fatal, limitations of such an approach.

If I had to pick one song known to me as the saddest ever (which avoids the major problems associated with judging the quality and the qualities of songs by things like Billboard charts or Grammys), that would be the “Aria” from the Goldberg Variations. The Goldberg Variations might not have words, but right at the top of the score it says “Song” (albeit in Italian).

Song samples and more pondering, after the jump. Continue Reading →

Hyperion Knight at the Alexander Piano

What is it about Australians, New Zealanders and Tasmanians and grand pianos??? At the ripe age of 15 years, Adrian Mann asked his piano teacher how long a piano bass string would have to be, not to require a copper wire over-wrap (to add mass, and thereby lower the resonant frequency). Her answer was, “Very long.” Over the next several years, young Adrian taught himself to build a piano almost entirely from scratch; the result is nearly 19 feet long. He is now doing business under the name Alexander Piano. Hyperion Knight was on tour in that part of the world, and so he stopped in, with the above result. There are two other Hyperion K. videos on Alexander Piano’s YouTube page.

# # #