JBL L100 Classic Loudspeaker

Photo by John Marks

Photo by John Marks

JBL’s L100 Classic loudspeaker has a United States MSRP of $4000/pr. (stands not included).

However, if you want to make them sound like the proverbial “a million bucks,” here’s how to do it:

(1) Connect a pair of JBL L100 Classics to your amplifier.

(2) Subscribe to the Qobuz streaming service (they have a risk-free 30-day trial offer). Feed that signal to your Digital to Analog Converter.

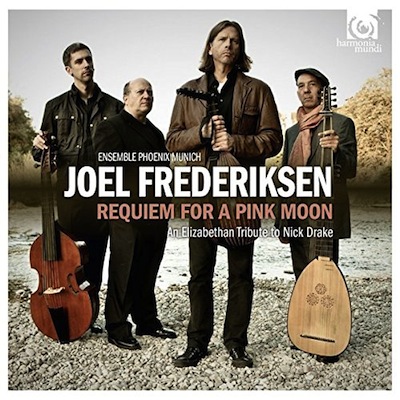

(3) Dial up the 24-bit hi-res version of Joel Fredericksen & Ensemble Phoenix’s astonishing feat of creativity and musicianship, the Nick Drake tribute album Requiem for a Pink Moon.

Wow. The first 60 seconds of Track 1 should convince you. The L100s sound like a million bucks. I unhesitatingly recommend audition of the L100 Classic to anyone shopping for loudspeakers in their price tier.

However, my take on the reality (of all such situations) is that every loudspeaker ever designed incorporates tradeoffs. To get this, you have to give up that. Even if the only thing you are giving up on is affordabilty.

The L100 Classic is remarkably affordable, considering its dynamics and its bass performance. If I were still writing for Stereophile magazine, I’d put it in for the coveted “$$$” high-value indication in the Recommended Components List.

But when you design a loudspeaker that has perhaps 80% of the bass and dynamics of loudspeakers costing four or five times as much (or even more; I am talking about loudspeakers in the $15,000 to $28,000 range), but at 20% of the cost of the more expensive loudspeakers, there are, of course, going to be tradeoffs and compromises. That’s my take on the reality.

More on Pink Moon, more on the social and cultural context of and the impact of the original L100, and more comments on the sound of the new one, after the jump.

Requiem for a Pink Moon is the kind of recording that justifies the expense of a great stereo system—because a great stereo system can deliver the “shock of recognition” when you hear a breathtakingly natural recording of the human voice.

I have compiled a Qobuz playlist entitled Classic Albums for the JBL L100 Classic Loudspeaker. Most of that music is music that would have been “in the air” during the 1970-to-1978 production run of the original version of JBL’s now-Classic L100. But the first album pick is Requiem for a Pink Moon, to make it easy for you to find it.

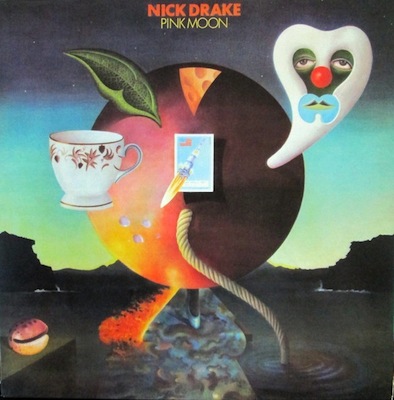

I vividly recall the release of the original Nick Drake Pink Moon LP—the album that Joel Fredericksen’s album is a tribute to. That was in 1972. On the Brown University campus, there was a cooperative coffee house that also sold records—the Big Mother Coffee House, and Mother Records. They had an impressive stereo system with IIRC some large Klipsch loudspeakers, but I don’t believe that they were Klipschorns proper.

A staff member would choose an LP to demo, cue it up, and prop the LP jacket up on a little easel, so that you would know what was playing. The big stereo was also the PA system when amplified musicians were playing in the coffee house.

The first time I saw the Pink Moon cover, while listening to Drake’s rather forlorn voice, my immediate reaction was that “This young man is not long for this world.” The cover art was in a rather creepy Surrealistic style.

Nick Drake died in 1974 (at age 26) from what very well might have been an accidental overdose of anti-depressants. His parents chose for his gravestone a quotation from his song “From the Morning”:

Now we rise

And we are everywhere.

How tragic for parents to have to choose an epitaph for their child’s grave marker.

The early-to-mid 1970s are sometimes thought of as a fallow period in the history of popular music. After all, the Beatles had released Abbey Road in 1969; but then, in 1970, the Beatles broke up. For some people, the world might as well have ended.

And, to that view, things later would only get worse. Much worse. I can easily imagine Karl Marx’s quipping, “Waiting for Godot is a tragedy; Waiting for Disco is a farce.”

One must admit that there was a lot of dopey or even borderline-toxic music released in the 1970s, even before the advent of Disco. Cases in point: “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero,” “Seasons in the Sun,” and “(You’re) Having My Baby”). But that can be said for almost every age. The 1970s were, in truth, a musically fertile and very diverse era.

I am indebted to Don and Jeff Breithaupt’s Precious and Few: Pop Music in the Early ‘70s for the startling, thought-provoking aperçu that for the five years from 1966 to 1970, all of the United States Top 100-chart No. 1 hits were accounted for by no more than 13 artists. That’s 260 weeks of charts! Whereas, over the next five years (1971 to 1976), the number of different artists with a No. 1 hit more than doubled.

The irony is that because of the “Shazam Effect,” the music business today has unprecedented information about what people like, and hastens to provide more of the same, and not anything that is too much different. Today’s 10 best-selling tracks have far more market share than did the Top 10 singles of 10 years ago; approximately 75% of the total revenue from sales of recorded music today goes to the top 1% of artists and bands. So the music scene of today more resembles the music scene of the mid-1960s, than that of the mid-1970s.

In the same month (January 1974) that Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark was released, these other artists also released LPs that charted: Bob Dylan, Blue Magic, Brian Eno, Foghat, Harmonia, Hot Tuna, Gordon Lightfoot, The Love Unlimited Orchestra, Graham Nash, Gram Parsons, Elvis Presley, Linda Ronstadt, Leo Sayer, Carly Simon, Grace Slick, Rod Stewart/Faces, Barbra Streisand, and Bobby Womack. And that’s only one month’s worth of new releases.

The early-to-mid 1970s saw the finest work of Stevie Wonder, Paul Simon, James Taylor, Gordon Lightfoot, Marvin Gaye, Roberta Flack, Janis Ian, and (arguably, at least) Joni Mitchell. One of my favorite little vignettes from that era is that when he accepted his Grammy Award, Paul Simon thanked Stevie Wonder for not having released an album during the previous year. Other singers and bands, whose time had not quite yet come, such as Steely Dan, got their starts.

I have written about the historical, social, and cultural contexts of home audio before, so I will only briefly recapitulate my contentions; you can click through for more in-depth explanations:

The place of component audio in society from the 1950s through the 1980s was part of the vision of “the good life.” But component audio was also inextricably intertwined with then-prevailing social mores about dating, mating, and family formation. I think that back then, a lot of audio equipment was bought by young men who didn’t really care all that passionately about music or sound—it just kept them from having to answer an embarrassing question once they got the girl back to their apartment [or dorm room]: “Where is your hi-fi?”

There were many reasons for component audio to have had its Golden Age in the 1970s. The prime reason was that there was an unprecedented amount of great popular music being recorded. Also, popular music on vinyl LPs did not have much competition for peoples’ entertainment attention spans or dollars. Furthermore, the music being recorded was increasingly sophisticated in terms of audio fidelity and production technology. Finally, fans of the music were willing to spend serious money to enter into the experience provided by recorded music more deeply, by listening on pieces of equipment with greater capabilities.

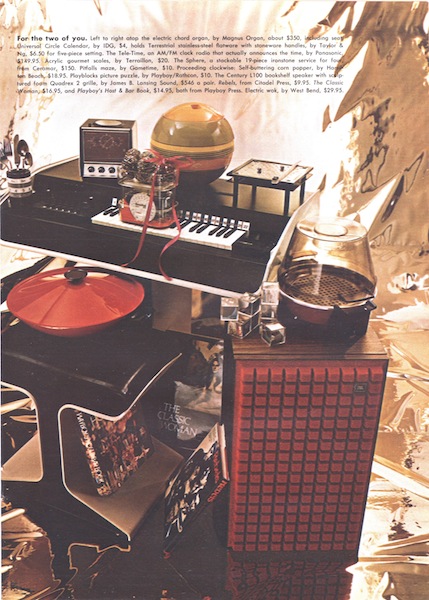

So, into that time and place, and into that cacophony of competing Weltanschauungen, the JBL L100 fell like a thunderclap. The January 1972 issue of Playboy magazine included a last-minute holiday gift-shopping guide. That sounds a lot less like a goof if you are aware that traditionally, in magazine publishing, the “cover date” of a magazine issue is the date when a magazine should be pulled off the newsstand rack and sent back. So, the January 1972 issue of Playboy was delivered to homes in early December 1971, when there was still ample time to go shopping.

The 1971 price of the Century L100 “Bookshelf” (bookshelf—yeah, right) loudspeaker with Quadrex 2 grille was $546 the pair. That’s about $3500 in today’s dollars, but please keep in mind that the new model uses updated technology in drivers and crossovers. For comparison, in 1971, the original Advent loudspeaker was $224 the pair, but the Advent was a smaller and simpler design.

One might even assume that the person who planned this photo essay for Playboy did not even bother to listen to the L100s. First of all, by that time, JBL’s reputation (love them or not, JBL was the paragon of the “West Coast” hi-fi sound) was firmly established. Furthermore, there was nothing else on the market with such a visually arresting grille. Here’s today’s version:

Harman International

Harman International

The L100 was a consumer version of JBL’s 4310 professional studio monitor. Both loudspeakers were three-way ported enclosures with 12-inch woofers. The first I saw an orange, cubed-foam grille on a loudspeaker was inside the gatefold album cover of James Taylor’s Mud Slide Slim LP. A liner-note photo showed one of the L100’s smaller siblings, the L82, that had been tied with a hefty manila rope to a wooden post at the desired listening height. One assumes that that was in a post-and-beam structure where some of the recording work had taken place. My younger self thought that that loudspeaker looked so cool. And later, in college, an acquaintance had a pair of the smaller L82s, complete with orange grilles. Those actually did fit into the dorm-room bookcase.

But an impressive bookcase indeed it would be, that could accommodate the L100’s dimensions of appx. 25 x 16 x 15 inches, and weight of almost 60 pounds each. With external dimensions of 25 x 16 x 15 inches, each L100 displaces approximately three and a half cubic feet(!!!). That is in the context of the equally classic BBC “two-cubic-foot” monitor, the BC1. So, the L100 is nearly twice as large as what was in the day considered a large loudspeaker. But bookshelf? Nyet, Tovarisch.

And, to get ahead of myself for a bit, were I to buy a pair of L100s, I would ask a custom furniture builder to build low, wide, deep one-shelf bookcases with small battens along the rear and side edges of the top, to keep the loudspeakers in place. The design height would be worked out so that the new L100’s titanium tweeter would be at the height of one’s ears, while seated in the listening position. This would also have the (perhaps only psychological) benefit of having the loudspeakers vertical. The optional metal stands ($300 the pair) were cool in their own way, but I always need more places to put magazines and books.

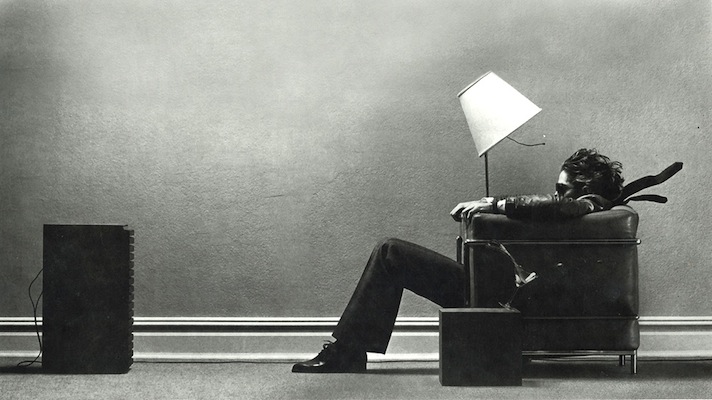

If the Audio Engineering Society (AES) ever gave out awards for “Iconic Industrial Design in Consumer Electronics,” the first one would have to go to the original JBL L100. Most people, at least most people of a certain age, remember the 1980s Maxell audio-casssette print and broadcast ad campaign featuring the “Blown-Away Guy.”

It’s still impressive today. I love the fact that somebody bothered to scare up a Le Corbusier “Grand Confort” club chair for the photo shoot. I wonder how they managed the Martini-glass special effect, in those pre-Scitex days. The mise-en-scene of the photo is so persuasive that 98% of the people probably never stopped too wonder, “Hey! Why is he listening to only one loudspeaker?” At least they bothered to dummy up some loudspeaker wires… this was before loudspeaker “cables.”

The Maxell “Blown-Away Guy” ad campaign is one of the most-frequently-parodied ad campaigns from its era. My favorite parody is cartoonist Charles Rodrigues’ Stereo Review captionless panel.

I love it that Rodrigues pictures his oldster wearing striped trousers, a cutaway coat, and waistcoat and tie, to listen to music in his own home. In a deep Chesterfield chair, rather than in a Le Corbusier. Somehow, I don’t think this old guy is grooving to Ornette Coleman’s then-latest LP… .

I love it that Rodrigues pictures his oldster wearing striped trousers, a cutaway coat, and waistcoat and tie, to listen to music in his own home. In a deep Chesterfield chair, rather than in a Le Corbusier. Somehow, I don’t think this old guy is grooving to Ornette Coleman’s then-latest LP… .

JBL’s publicists arranged to have a pair of the new L100 Classics delivered to me. The loudspeakers plus stands arrived via truck freight, on a pallet. I did manage to unbox them safely with no help; but, a second person would have made it easier. These are very heavy loudspeakers! Very solid, too. The only wood-veneer choice is Walnut. The famous grilles are available in Black, Blue, and Hot Pink. Erm, that was just to see if you were reading carefully. The third choice is (Burnt) Orange, but you probably already knew that.

I set the loudspeakers up as shown in the top photo, with my laptop streaming Qobuz to the optional DAC card in the Moonriver 404 integrated amplifier. BTW, the laptop screen in that photo shows an Amadeus Pro II waveform. The USB cable (from the laptop to the Moonriver 404’s optional DAC card) was from Wireworld, their Starlight 8 USB 2.0 (MSRP $100/1m). The loudspeaker cables were also from Wireworld, their Mini Eclipse 8 (MSRP $660/3m pr.). Wonderful stuff, and very fairly priced.

I did hit the L100 Classics a few times with the Ayre/Cardas Irrational, But Efficacious! sine-wave sweep, and the results were very gratifying. I got the idea that this pair was well-traveled (it apparently had been in Holland at one point) but perhaps it had not had much recent use. BTW, the L100 Classics are manufactured in Indonesia. After a few courses of the sine-wave sweep, the L100s sounded pretty darn good!

One would have to have a heart of stone not to indulge in a few hours of “Guilty Pleasure & Nostalgia” listening, once one has loudspeakers as dynamically capable as L100s set up in one’s listening room! (I exceeded 100 dBA on peaks, only a few times.)

In short order, I heard the entirety of Rumours, the entirety of the Doobie Brothers’ Minute by Minute, the entirety of Silk Degrees, Norah Jones’ “One Flight Down,” Gordon Lightfoot’s “If You Could Read My Mind,” “Stairway to Heaven,” “Say You Love Me,” Al Stewart’s (single) “Year of the Cat,” Toni “Braxton’s “Unbreak My Heart,” Sade’s “Smooth Operator,” Jackson Browne’s (single) “Late for the Sky” and “Fountain of Sorrow,” and even (brace yourselves) A-ha’s “Take On Me,” and… Hanson’s “MMMBop.” Purely for research purposes, of course.

I enjoyed every minute of it! Miles of smiles. And lest anyone is sniffing that I am hopelessly trapped in the past, I listened to a lot of Tidal’s Vulfpeck playlist. If you don’t know them, Vulfpeck is a contemporary funk/jam-band who take their inspiration from the studio ensembles of the past, such as the Wrecking Crew, Muscle Shoals, and Booker T. and the MGs. Their recordings are so clean and sweet!

I then set about creating a Qobuz playlist of albums from the era when the L100 first-generation loudspeaker was new. I did not limit myself to songs that were released 1970 to 1978. My rationale was that in 1970, there were lots of albums from 1969 and earlier that were still getting listened to, a lot.

And, as previously mentioned, I was so knocked out by the L100s’ playback of Requiem for a Pink Moon that I put that in first position. There was just so much tactility to the sound. Here’s the first minute of Requiem for a Pink Moon, as I referred to far above:

1. Road (Nick Drake)

Other real sonic standouts were “One Flight Down,” “Fountain of Sorrow,” and “If You Could Read My Mind.”

I think that a lot of the credit for the tactility of the L100’s sound goes to its 5-inch pure-pulp midrange driver. There are pluses and minus on both sides of the 2-way vs. 3-way divide. Two-ways allow for a simpler or even a minimal crossover, but three-ways have a dedicated driver handling the band where most of the “intelligibility” of music lies. BTW, the L100 has Level controls for both Midrange and Tweeter. I usually left them in the factory settings, and I usually listened with the grilles off. I actually stood the grilles in front of the fireplace doors, intending to reduce early reflections off the glass.

I also must mention that similar to the midrange driver, the L100’s 12-inch woofer’s cone is made from pulp, rather than some kind of plastic or composite. I think that having woofer and midrange made from the same material can only help integration. And let me dwell for a moment on the significance of the woofer’s size.

While a 12-inch woofer has a diameter twice that of a six-inch woofer/mid, it is the comparison of the frontal areas that really tell the story, because it is the frontal area that provides the “push.” A six-inch woofer/mid has a frontal area of 28.26 square inches. But a 12-inch woofer has a frontal area of 113 square inches. The 12-inch woofer is four times as large, in frontal area. That’s why there’s really no comparison.

Here’s the playlist:

| Requiem for a Pink Moon

Abbey Road |

Joel Fredericksen / Ensemble Phoenix Munich The Beatles King Crimson Procol Harum Fairport Convention Marvin Gaye Van Morrison Tom Rush Santana Rolling Stones Led Zeppelin James Taylor Dan Fogelberg Bruce Springsteen Hall & Oates Jackson Browne Boz Scaggs Al Jarreau Michael Franks The Doobie Brothers Gordon Lightfoot |

___ 2012 1969 1969 1969 1969 1970 1970 1970 1970 1971 1971 1971 1972 1973 1973 1974 1976 1977 1977 1978 1978 |

(I know that the above list represents more than 15 hours of listening. Try listening to just one album a night, for about two and a half weeks.)

Some of these albums are indisputably household-name albums: examples being Abbey Road, Sticky Fingers, and Led Zeppelin IV. Others will be somewhat familiar, but perhaps a bit neglected today: In the Court of the Crimson King, Abraxas, A Salty Dog, and Mud Slide Slim are examples. But a few of the other albums might be known only to their diehard fans, so I want to point those out to you.

Fairport Convention was, in its day, a semi-successful, critics’-darling, folk-rock band. The fact that Led Zeppelin invited Fairport Convention vocalist Sandy Denny to sing a track on Led Zeppelin IV, I think, indicates the respect their peers held them in. That, and the fact that Unhalfbricking (supposedly the album name was a word made up in a word game) included several previously-unreleased Bob Dylan songs. Oh, and that their guitarist was Richard Thompson. Worth a listen, I’d say.

Tom Rush was an also-ran in the 1960s-1970s Singer-Songwriter Sweepstakes, but I think he had a better voice than James Taylor, and also that he had at least as much to offer as an interpreter. Wrong End of the Rainbow is perhaps his finest work.

The singer-songwriter phenomenon reached a high-water mark in the “Sensitive Male” Sub-Category with Dan Fogelberg’s début album Home Free. Fogelberg combines intelligent lyrics with rewardingly-acoustical production values, delicately tinkly pianos, and a nearly weightless falsetto voice… Home Free will either work for you, or it won’t. But before you give up on it, please listen to “The River.” There’s a lot of Neil Young in that song. After all, it was the early 1970s. Home Free was recorded in Nashville, which means it was one of the singer-songwriter albums recorded there in the wake of Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde.

Al Jarreau’s live-in-Europe Look to the Rainbow is that rarity, a true jazz-vocal album. Jarreau’s later success as a crossover/pop artist should not cause people to forget this album, which won the Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Album. Jarreau’s tight little road band included Abraham Laboriel (he worked with Madonna, Michael Jackson, Ray Charles, Quincy Jones, and Stevie Wonder) on Autoharp. Well, actually; on electric bass, but you already knew that. Don’t miss this fabulous music and singing!

Sleeping Gypsy is the album Cole Porter would have made, if he had been young and in Los Angeles in the early 1970s. Somewhere in Heaven, I am sure that Cole Porter split his pants, when he heard Michael Franks’ Porteresque couplet

I hear from my ex—

On the backs of my checks.

In terms of both the session musicians and the general musical style there’s some degree of overlap between Sleeping Gypsy, and Court and Spark, and also Aja. So, if you like either or both of Court and Spark and Aja, you will probably also like Sleeping Gypsy.

Endless Wire was, in my opinion, both the album where Gordon Lightfoot “went electric,” and his last great album. Great songwriting, great singing, and great (Nashville Visits Canada) production values. If there is a more poignant “Divorce Song” than “If Children Had Wings,” I don’t want ever to hear it. And “The Circle is Small” is one of the best “Cheatin’ Songs” by a Canadian. (tee hee.)

So, John Marks: What do we tell the music lover who has $4000 to spend on a new pair of loudspeakers?

As I mentioned above, the JBL L100 Classic delivers amazing bass and dynamics for the money. But there are also tradeoffs when you offer 3.5-cubic-foot loudspeakers weighing 58 pounds each, for the same kind of money other companies charge for a pair of two-way monitors you could carry, one tucked under each arm. (But the advantage of such speakers is that almost any bookshelf can hold them!)

I found the L100s to be all of, listenable, musical, and (very) capable of creating emotional engagement. However, there’s no free lunch; and anyway, the L100 is not the most expensive high-end loudspeaker in JBL’s catalog, by far.

The areas where the L100 did not quite measure up to loudspeakers costing four or five times as much, will probably not surprise anyone. They lack the last degree of resolving power. Other, more expensive, loudspeakers are more coherent. Other, more expensive, loudspeakers create more well-defined individual images in a more dimensional soundstage.

But if you quickly look over the kinds of loudspeakers that do better in those areas, over and above costing a lot more money, and regardless whether the maker is Wilson Audio or Wilson Benesch or Vivid Audio, what those loudspeakers have in common is high-tech materials, radical enclosure design, and exotic-tech drivers.

No loudspeaker in that performance category today is based on a wooden box that was designed in 1969.

The fork in the road for the “L100-Curious” is whether the tradeoff works for them.

If you listen mostly late at night to harpsichord music, and in an apartment building where you have to “keep it down,” the L100’s strengths won’t do you much good.

However, if listening to classic rock on 6-inch two-ways makes you feel unfulfilled, then, by all means, arrange for an audition, or just order a pair.

For what the JBL L100 Classics are, I loved them. I am very sure they will make the right listener very happy.

Here’s JBL’s Dealer Finder. And, Music Direct in Chicago sells them online. Music Direct has a returns policy that I believe is generally regarded to be very fair.

To sum up: Highly Recommended

JBL L100 Classic Loudspeaker

Country of Origin: Indonesia

US MSRP: $4000

JBL (Harman International)

www.jblsynthesis.com

(888) 691-4171

Other contact information

# # #