Month: August 2020

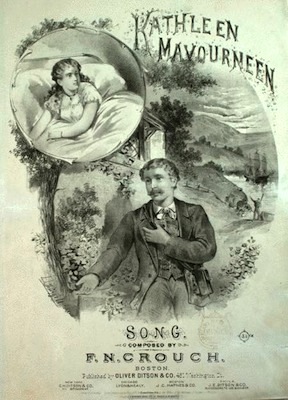

Cantor Meir Finklestein, Grant Geissman: “Kathleen Mavourneen”

Despite my Jewish surname, I had such a provincial, parochial, cloistered Irish-immigrant upbringing that when my mother’s aunts did not want the tykes to know what they were talking about, they spoke Gaelic.

Even better: As a precocious reader of the newspapers, I thought that I had figured out that Black Nationalist leader Malcolm X was, in reality, Pope Malcolm the Tenth.

Hey! I was a middle child! They never explained anything to me.

John XXIII, Malcolm X—they both were religious leaders who had Roman numerals instead of last names… .

Anyway, the sad Irish ballad that breaks the treacle meter (despite having been composed by an Englishman), is “Kathleen, My Darling.” In Gaelic, “Kathleen mo mhuirnín,” which Anglicizes to “Kathleen Mavourneen.” So, “Mavourneen” is not a family name (last name), but rather a term of endearment. I had always assumed it was a folk song, silly me. However, a quick look at the sheet music indicates otherwise; the melody takes slight turns here and there that are not really “folk-ish.” Actually, more like early-19th-c. German art music. Imitative of Irish or Scottish folk music, but still German art music. (FWIW & YMMV.)

Continue Reading →

Julian Bream: Nocturnal After John Dowland (conclusion) (Benjamin Britten, op. 70)

Julian Bream (who died today, age 87, in Wiltshire, England) grew up in a musical household, and certainly made the most of it. His father, a commercial artist, was a jazz guitarist who also played the piano. As a child, the young Julian would sit by the radio, trying to strum along on his father’s guitar. Lessons followed on both guitar and piano. Winning a piano competition at age 12 gave Julian entry into the Royal College of Music. He made his début recital on the guitar at age 13, and made his Wigmore Hall début at age 17. His father bought him a lute, which he taught himself to play. In 1960, he founded an original-instruments group with himself as lutenist, bringing Elizabethan music to widespread public awareness. England’s most important composers, Benjamin Britten, Sir William Walton, and Sir Michael Tippett wrote pieces for him, as did dozens of other composers.

Here he is in a video from 2003 (I believe), playing the penultimate and final movements of Britten’s Nocturnal after John Dowland. Britten’s Nocturnal is not so much a set of variations as an 18-minute reconstruction of a deconstructed “Come, Heavy Sleep,” by John Dowland.

In sharp contrast to the usual variation sets that start with the melody and get more complicated as they go on, Britten inverted that agenda. The piece starts with the variation most remote in character; each successive variation is closer to the original tune, and the work ends with Dowland’s original lute song (which was published in 1597). So, here we have the final variation, and then the statement of the melody.

There were giants in the earth in those days…

# # #